Why you're failing on LinkedIn

LinkedIn is dying, but before it dies, it'll extract as much value as it can from people who think it's thriving and growing.

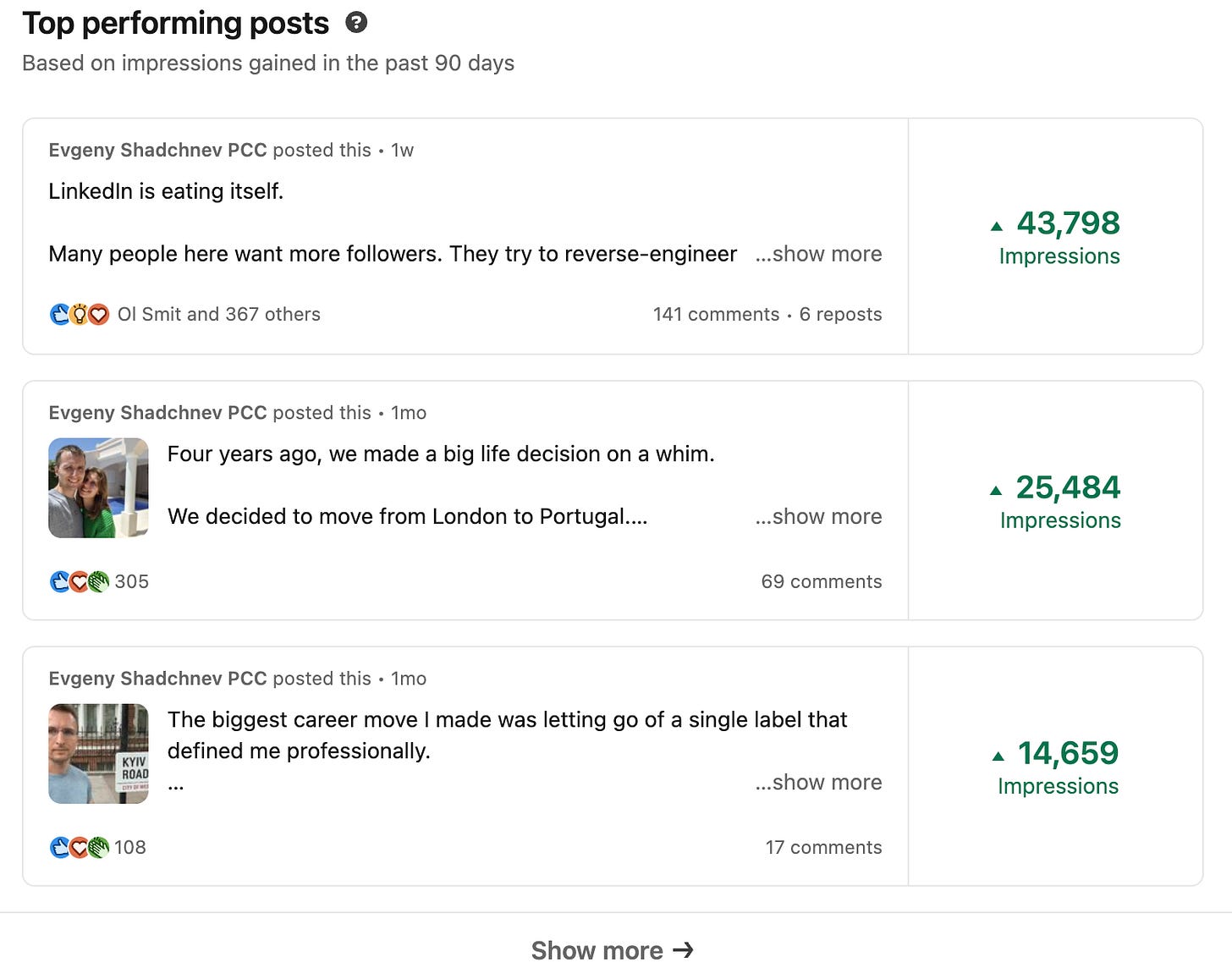

Something I wrote on LinkedIn resonated with far more people than I expected.

LinkedIn is eating itself.

Many people here want more followers. They try to reverse-engineer what gets likes and comments and write engaging posts.

There's a method to what "works" today: generic inspirational advice, selfies, clever opening lines that catch your attention, short sentences, etc.

But such content is hardly ever deep. It's intellectual candy: sugar-loaded and free of nutrients. It's rare that I come across a piece of content that is deep enough that I want to re-read and save for later. When I do, it often has just a few likes.

It's understandable that content that evokes emotion will win over content that prompts actual thinking. But the consequence is that there are fewer and fewer genuinely interesting pieces here.

Everyone wants someone else to read their content on LinkedIn, while they themselves want to spend less time on the platform — and that includes me.

This dynamic can't be leading in a healthy direction.

I couldn’t quite say what I meant by “can’t be leading in a healthy direction,” but I was frustrated by LinkedIn’s feed becoming increasingly shallow and curious about many of my friends’ massive investment into building a personal brand there.

But most of all, I was perplexed by my own inability to figure it out. Whether I tried to post something insightful and original, follow the latest LinkedIn hacks, or post stupid jokes, my following on the platform seemed to grow more or less randomly.

It felt like the game was rigged, like a casino: not that you can’t win money there, but if you’re trying to outsmart the casino, you’d better be damn world-class smart, and I’m certainly not.

But I’m smart enough to eventually realise that learning to make money playing roulette from those who won big there isn’t a great strategy.

Looking at impressions statistics on LinkedIn and trying to figure out what I’ve done to make a post do well or not reminded me of seeing roulette displays in Las Vegas casinos:

To anyone except possibly drunk roulette players and gambling addicts, it’s evident that roulette numbers are random. Yet, I remember looking at the screen and thinking, “It’s been five red numbers in a row; the next one HAS to be black, right?“

That’s as deluded as it gets, and that’s how casinos make money. But the display screen is there precisely to trick players into thinking they know something the casino doesn’t.

Could LinkedIn analytics be just like the roulette statistics screen in some way?

I’m not suggesting, of course, that the performance of posts on LinkedIn is as random as a roulette. It’s not true: better content does better on average. Plus, those of us trying to build a personal brand there aren’t as drunk or deluded as an average late-night Las Vegas gambler.

But there’s some sophisticated trickery going on. Just like the house always wins in Las Vegas, the house always wins on LinkedIn, with some big winners among punters and many losers hoping to outsmart the house.

Thankfully

pointed to Cory Doctorow’s essay about enshittification of social media platforms in the comments to my post. The essay is brilliant and worth reading, but here’s the gist of the argument and how it applies to LinkedIn today.How LinkedIn wins at your expense

First, let’s look at the big picture. In Cory’s words:

Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.

I call this enshittification

First, LinkedIn was genuinely useful to its audience. It was great to connect with fellow professionals, away from the holiday pics on Instagram and neighbours’ posts on Facebook.

Then, LinkedIn started to optimise its model to make as much money from recruiters as possible. Okay, fair enough. It still wasn’t bad for us non-recruiters, not least because those recruiters were hiring everyone else, and that’s not a bad thing.

Then, LinkedIn started extracting value from the audience at the expense of the quality of content or interactions. In the long term, this will kill LinkedIn, but in the short term, it will drive up engagement and force lots of smart people to produce “engaging” content for free. Quoting Cory, again:

This is enshittification: surpluses are first directed to users; then, once they're locked in, surpluses go to suppliers; then once they're locked in, the surplus is handed to shareholders and the platform becomes a useless pile of shit.

First, LinkedIn was good for regular users and recruiters. Once they were locked in, LinkedIn was good for content creators. Once they’re locked in (because if your business depends on you having a “personal brand” there), the platform starts extracting the value for itself, making the experience shit for both users and creators until it becomes irrelevant.

Once you understand the enshittification pattern, a lot of the platform mysteries solve themselves. Think of the SEO market, or the whole energetic world of online creators who spend endless hours engaged in useless platform Kremlinology, hoping to locate the algorithmic tripwires, which, if crossed, doom the creative works they pour their money, time and energy into

But how exactly does LinkedIn extract the value? By fooling people into believing that they control more than they actually do, just like gamblers think they can predict the roulette wheel by looking at the last few numbers.

I can’t come up with a more brilliant metaphor than the one Cory offered:

If you go down to the midway at your county fair, you'll spot some poor sucker walking around all day with a giant teddy bear that they won by throwing three balls in a peach basket.

The peach-basket is a rigged game. The carny can use a hidden switch to force the balls to bounce out of the basket. No one wins a giant teddy bear unless the carny wants them to win it. Why did the carny let the sucker win the giant teddy bear? So that he'd carry it around all day, convincing other suckers to put down five bucks for their chance to win one

In other words, LinkedIn deliberately allows some people to win big, creating a massive following in a way that looks like it wasn’t random and helping them monetise it. This effectively enlists them to work hard recruiting the next generation of content creators, hoping to achieve the same.

It’s a kid with a giant teddy bear explaining to other kids how to throw balls into the basket to win their own teddy bear. If they win, it’s because they “learned”; if they don’t, they didn’t throw well enough. Obviously.

The carny allocated a giant teddy bear to that poor sucker the way that platforms allocate surpluses to key performers – as a convincer in a "Big Store" con, a way to rope in other suckers who'll make content for the platform, anchoring themselves and their audiences to it.

I’m not saying you can’t “win” building a personal brand on LinkedIn. Just like I’m not saying you can’t win big money playing roulette. Some will. But it doesn’t strike me as a reliable winning strategy.

Where do we go from here?

First, good content still matters. Regardless of the enshittification of various platforms, if you’re creating content, try to make it good to attract people who care and deepen your own thinking, even if it will be read by fewer people who’ll click “like” under yet another post about the Eisenhower matrix.

Second, understand the dynamics of the enshittification of platforms. There are no evil players here. LinkedIn employees are not evil. Those building personal brands on LinkedIn are not evil. Those helping them are not evil. Everyone is trying to do their best and help others and themselves. Cory (and I) are writing about an overall dynamic of the system that, over time, makes enshittification far more likely than an increase in quality. It happened to Twitter, Facebook, TikTok, LinkedIn and many others — details in Cory’s essay.

Third, whenever possible build a direct relationship with your audience: email lists, communities on dedicated platforms like Substack, Patreon, Mighty, Slack or even Whatsapp. And if and when Substack becomes enshittified, be ready to move on.

Most of all, if you’re having a sense that you’re just a few steps away from “figuring out” how LinkedIn works and you just need to work a bit harder and learn a bit more, consider that that’s exactly how gambling addicts feel looking at the roulette statistics screen. LinkedIn is just a more sophisticated game for more sophisticated people.

But in the end, the house always wins.

Evgeny, this is the kind of reason that you and I have always resonated. I have never liked the platform and the notion of having to engage simply because it is the business version of Facebook or the like has never sat well. A very elegant summation of this platform and really all the others.

Great post Evgeny, very timely as well for the majority of us.