The AI Blind Spots Even Smart People Have

And why I'm less certain about this technology the more I use it.

As I prepare for Full Stack Founder AI Bootcamp (29-30 September in London, get your tickets here with discount code EVGENY100), I've been thinking about common things intelligent people miss about AI.

I already wrote about some of them in a previous post, but there are a few more that keep nagging at me. Perhaps "miss" isn't even the right word. But we all seem to grab onto different parts of this thing, each convinced we understand it, when really we're all partially blind.

The patterns I keep noticing

When smart people talk about AI, I notice they tend to reduce it to something manageable. AI becomes chatbots. Or it becomes "just" pattern matching. They look at today's limitations and assume they’ll still be here tomorrow. They assume their experience with the technology is representative of everyone else's.

I've certainly been guilty of all of these myself.

We keep equating AI with chatbots

Often, when we talk about AI we equate it with chatbots: ChatGPT, Gemini, Grok, Claude, DeepSeek. I was listening to a podcast on AI last night that never ventured beyond the chat interface (thanks for the recommendation Adriá!).

But this is like equating electricity with light bulbs. Sure, light bulbs don't work without electricity and they may be the most visible and transformative application of electricity. Yet it also powers everything from pacemakers to particle accelerators.

Likewise, AI as a general-purpose technology can power a chatbot, but it's also folding laundry (badly, but improving), discovering new antibiotics, creating photorealistic virtual worlds in real-time, and powering autonomous weapons systems.

Chatbots are easy to use and understand. But I wonder if it's making us miss the forest for a particularly charismatic tree.

The "just pattern matching" dismissal

A common argument that keeps surfacing is that AI is doing "just" pattern matching. It's "just" finding plausible outcomes given the immense data it was trained on. Because of this, the argument goes, AI systems aren't capable of "real" understanding or "real" creativity.

I find myself going back and forth on this one. There's something to the philosophical question of whether pattern matching can constitute understanding. (Though I sometimes wonder if my mind is doing much more than pattern matching itself.)

However, AI can act in the real world. It writes and executes code, and code powers much of our civilisation. When an AI diagnoses a medical condition correctly, or when it controls killer drones, the philosophical question of whether it "really" understands becomes... well, academic.

The swarm of drones example might be dramatic, but it illustrates something important. If AI-powered systems are making real-world decisions with real-world consequences, the question isn't whether they truly understand, it's whether they work. And increasingly, they do.

Looking at today instead of tomorrow

AI is often criticised for its limitations today. I do this myself, pointing out hallucinations, context window limitations, tendency to overcomplicate. But I keep forgetting that I'm looking at a technology in motion, not a finished product.

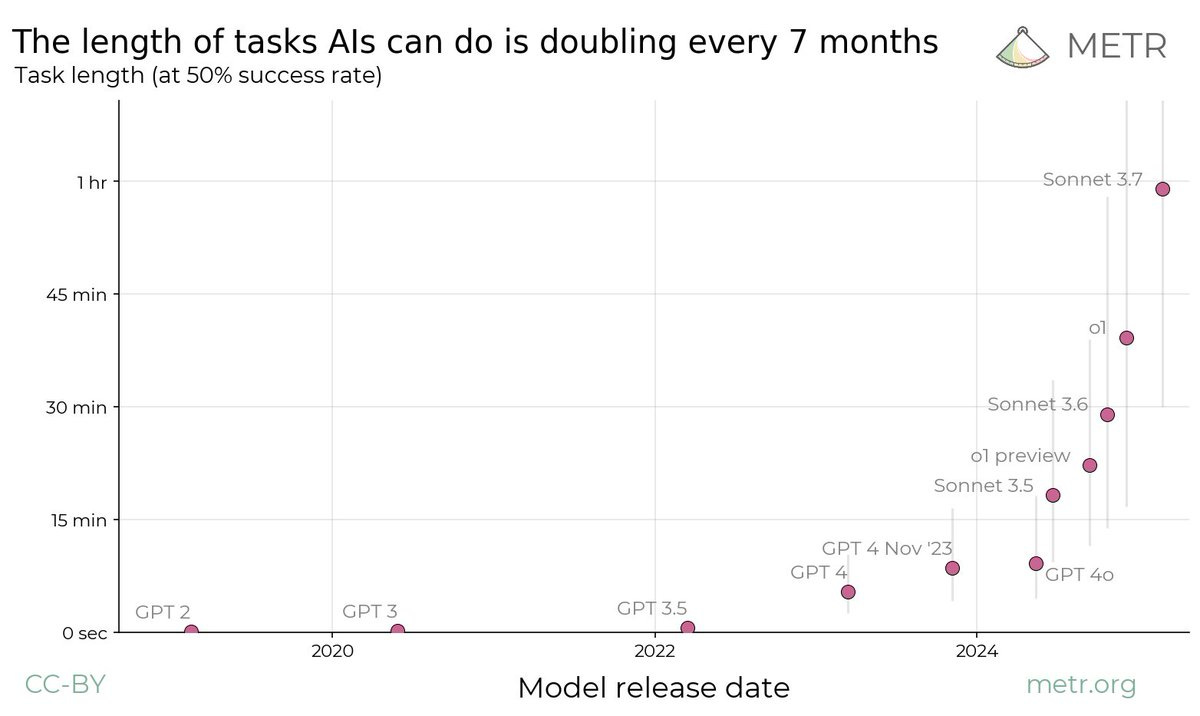

I remember this observation from Azeem Azhar: the length of tasks AI can autonomously complete is doubling every seven months. If this trend holds (and that's a big if), by 2027, which is closer than ChatGPT's launch, we could have AI handling eight-hour workdays with 50% success rate.

Three years ago, ChatGPT could barely write coherent paragraphs. Today, I'd argue it's a better software engineer than many people on the planet (including, most certainly, me). Whatever metric you look at — intelligence, autonomy, context size — we're on an exponential curve that shows no signs of flattening.

Yet I still catch myself thinking about AI's capabilities as if they're static. It's hard to think exponentially when our brains are wired for linear extrapolation.

The elephant problem

We all know the old parable about the blind experts and the elephant, each touching a different part and declaring they understand the whole. Of course, it’s a tired cliché, but with AI, it feels uncomfortably apt.

Some people use AI mostly for coding. Others for creative writing. Others for emotional support. Still others for data analysis or image generation. And each of us tends to think our use case represents the technology's essence.

I've been using AI primarily for coding and writing (and as a google replacement), but then I watched my Toby Stewart use it to make incredible ads and James McAulay launch advanced audio tools using AI. An 81 y.o. therapist praised ChatGPT as ‘eerily effective’ (I agree). And what Joshua Wohle is doing for personal productivity is on another level entirely.

No one has touched the entire elephant. I certainly haven't.

A dependency we might not see coming

I listened to a lecture by Dr. John Vervaeke the other day that contained an insight I can't stop thinking about.

Vervaeke argues that a core function of consciousness is what he calls "relevance realisation": choosing what to focus on from the infinite field of possible attention. At any given moment, we face a computationally explosive choice of things we could pay attention to. Somehow, without conscious effort, we filter this down to what matters.

When AI is trained on human-generated data, it inherits our collective sense of what's relevant. But if it lacks the ability to perform relevance realisation independently, that is if it can only mirror the relevance judgments baked into its training data, what happens when AI runs out of human-generated content to train on?

This isn't just academic speculation. It suggests AI might be fundamentally dependent on human consciousness in ways we don't yet understand. Not in some mystical sense, but in a practical one: without our continuous input about what matters and what doesn't, AI might lose its grounding in reality.

I don't know if this is right. But it caught my attention. Watch the lecture above if you’re curious!

Where this leaves us

I don't have neat conclusions here. The more I think about AI, the less certain I become about what it is and where it's going.

What I do notice is that the people who seem most certain about AI, whether they're evangelists or skeptics, tend to be looking at just one facet of it. The chatbot users who think it's the future of everything. The armchair philosophers who dismiss it as mere pattern matching. The coders who see it as a fancy autocomplete.

Maybe the appropriate response isn't certainty but curiosity. Maybe we need to keep touching different parts of the elephant, comparing notes, staying humble about what we don't know.

As I prepare for Full Stack Founder AI Bootcamp (29-30 Sep, London), I'm looking forward to both sharing what I've learned about building with AI and learning what others have discovered.

What have you noticed that the rest of us might be missing?

Book your ticket using the discount code EVGENY100.